Have I got SAD – or do I need to slow down?

What is Seasonal Affective Disorder – and do you have it?

How do you feel when the days start getting shorter? Do you experience a building dread of dark mornings, where you struggle to drag yourself out of bed? Do you look forward to being able to coorie in under a blanket when it’s gloomy outside? Or perhaps it’s not the lack of light that you find difficult, but the weather – not being able to soak up the sun like a solar panel prompts anxiety that your battery is going to run low.

Seasonal Affective Disorder – what does it mean?

SAD (Seasonal Affective Disorder) is a term used for feeling depressed, low in motivation and lacking in energy at certain times of the year. ‘Winter-pattern SAD’ is when people begin to experience symptoms in autumn and through winter, but some people also experience mood changes (anxiety, agitation) in spring and summer – ‘summer-pattern SAD’ – although this is less common.

The jury is still out on what exactly causes SAD – there are a number of factors indicated, including melatonin levels and vitamin D. People with a family history of depression are more likely to experience it. For some people, these changes in mood can be really debilitating, meaning that they experience severe symptoms of depression for almost half the year, so it can have a huge impact on their enjoyment of life.

Being human in the world

I’m absolutely not denying the reality of people’s experiences, or to suggest that you shouldn’t seek support for managing symptoms of depression, fatigue and social avoidance or anxiety. But for most of us, when we notice some changes in how we feel at different times of year, I wonder how helpful it really is to casually adopt a ‘disorder’ label.

I also wonder how much SAD is a product of a modern society that has evolved to a point where we need to ignore our bodies’ natural tendencies, in order to see ourselves as ‘operating productively’. The period where industrial and post-industrial society developed is the blink of an eye when compared to the timescale over which human animals evolve, and perhaps our bodies are struggling to catch up with the expectations of capitalism. Doing more than we have energy or capacity for (whatever the reason) ultimately leads to burnout and exhaustion – often manifesting as depression or anxiety.

The urge to see ourselves as somehow ‘other’ from the natural world has contributed to an inability to truly acknowledge the destructive impact humans have had on the world as a whole. Life as humans have come to live it in the 20th and 21st centuries has encouraged us to suppress our natural responses to the changes in the world around us – including regular, seasonal changes – to the extent that when we notice that we’re feeling differently, we try and make it ‘wrong’.

‘Disorder’ or natural response?

Following this line of thought, I wonder if there is a healthier, more compassionate approach to changes in mood and energy levels related to the shift into autumn and winter. Rather than asking ourselves ‘how can I feel more like I do in the summer?’ perhaps we can ask instead:

- How can I be more understanding of my changes in mood or energy?

- Where can I look for opportunities to live in the way that my whole self needs?

- What do I need in order to take care of myself so that I can be ‘well enough’ in the world as it currently is?

Let’s explore these questions a little bit more.

Bringing a compassionate understanding to our responses to seasonal change

The phrase ‘the natural world’ tends to be used to denote something separate from humans, and all human-created things. But human beings are animals, and it doesn’t serve us well to think that we don’t have the same basic needs as other mammals – eating, resting, mating, etc. We are still part of an ecosystem, although we collectively tend to try and distance ourselves from the rest of the world in an attempt to avoid the pain of acknowledging our destructive behaviours towards it.

In the Global North, until only a few hundred years ago, humans lived in a way that was much more responsive to the seasons. Our survival depended on us having a closer relationship with the land that fed us. Of necessity we needed to be much more active at certain times of year to produce, gather and store the food that would keep us going through the months of scarcity. While humans didn’t hibernate like some creatures (that are able to slow their body rates down in winter), the pace of life would have been slower over darker, winter months, where there was less to do on the land. Depending on food stores, there might be less food to provide energy for activity. I have a friend who works in a physical, seasonal job, who refers to the depths of winter as ‘plumping-up season’.

I also wonder how much we allow ourselves to live with the fluctuating energy levels that develop as part of the ageing process. Our bodies evolved to fulfil different roles at different life stages, and historically women wouldn’t expect to live for decades after our ability to procreate ceased. I’ve noticed that post-menopause, I tend to naturally want to be less active in the winter months. It’s difficult to know how much of this is connected to the changes in my body and energy levels, and how much is because I have learned to better tune into my body’s needs rather than overruling them.

Would you describe yourself with the words ‘I like to keep busy’? If so – have you ever thought about what that ‘liking’ is about? Many of us use busyness or activity as a coping mechanism – it distracts us and helps us avoid feelings. If we’re not being active we may start to feel anxious, and attach this anxiety to a ‘problem’ that we can then get busy trying to fix. If this rings true for you, then any natural slowing-down tendencies you may experience during winter months might feel a bit scary, because allowing yourself more space brings the potential for anxiety.

Living in the way that our bodies need

I’m fortunate to have moved myself to a career that allows me some freedom to dictate my working pattern through self-employment. In recent years I’ve come to realise that I have less energy towards the end of the year. I need to bear in mind, when planning ahead, that setting myself goals for the last quarter is unhelpful – I don’t achieve them and I end up feeling I’ve failed or ‘not tried hard enough’. I can structure my appointments so that most days I can squeeze in a quick dip in the sea, which particularly works for me in the winter as it gives me an intense burst of ‘outsideness’ when I may not feel motivated to go for a long walk.

Not everyone can dictate their working pattern or life to this extent; even if you recognise that your body would prefer you to have a different structure to your day, this may not be possible due to the requirements of your job or employer. However, most people have at least some autonomy to tweak aspects of day to day life – if they can allow themselves to recognise the value of prioritising their needs.

Ask yourself whether you really want to be more active or energetic in winter. Is that about your needs, or does it have the words ‘I should’ attached to it? Is it influenced by what you imagine others think or do; have you been affected by what you perceive as societal norms, or the ‘living my best life’ impact of social media? Most of us are influenced by these factors to some extent, even if we like to tell ourselves ‘I don’t care what others think’.

Modern society as lived in many countries is focused on productivity to a degree that is unhealthy for the planet and for us, creating a myth that economic growth is desirable and feeding fears of scarcity. It benefits the world when we do less, as well as allowing us to recover – and to save money. If you feel the urge to shop to ‘cheer yourself up’, try pausing for a moment and checking in with your inner self what need you might be trying to meet. How you might turn towards that part of you with kindness rather than trying to distract yourself from it by looking for external stimulation.

Taking care of ourselves ‘well enough’

We’re living, breathing creatures and how we feel changes depending on what’s going on around us, and the events and stresses that we’re subject to in our lives. That includes weather, daylight hours, temperature. Telling ourselves that we can carry on operating at the same capacity whatever happens around us, and to us, is a denial of reality and longer term isn’t good for us.

However, in order to carrying on living in society it’s necessary to accept that the modern world isn’t currently responsive to the needs of most of the world’s inhabitants (of all species). My ‘perfect world’ might not be the one I currently live in, and it’s important to recognise that, and allow myself to feel the grief of it, but I also have to find a balance that is ‘good enough’ for me to keep living in the world as it is.

I think of this as a little bit like the experience of being autistic in a world where the neurotypical experience is privileged. Autistic people shouldn’t have to do all the work to adapt to a society that often doesn’t work for them, but until society itself evolves to be more accessible and accepting to all, the choice for autistic people can sometimes be (unfairly) adapt or withdraw.

What might help develop self-compassion?

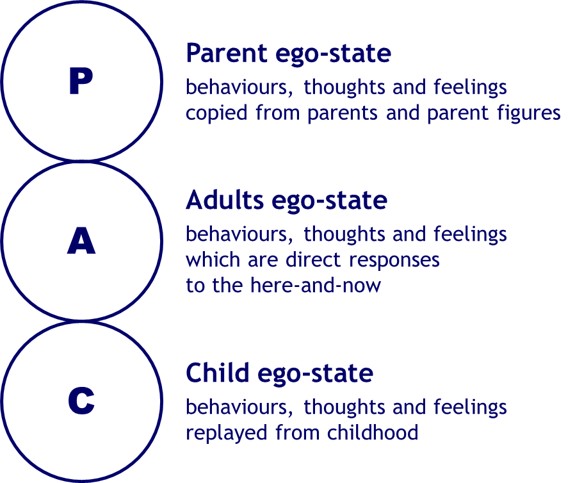

I use a Focusing practice to regularly check in to what I need. Although having a routine helps me, it can sometimes mean that I shut myself off from noticing when I need to slow down. I (try to) accept that I might not always know what I need, and that this will change from day to day – and perhaps more importantly, I give myself a break if I realise I’ve overdone it or made the ‘wrong’ choice. Learning to listen to what your whole self needs – rather than to the internal parent or inner critic that’s very good at telling you what you ‘should’ be doing – can be truly healing.

Treatments that are recommended for SAD are worth considering, but pay attention to what feels right for you, rather than trying to convince your body that it’s not really winter. For example, generally I’m an early riser and structure my work to suit this. For a few months of the year, though, my body would really like to wake later but it’s not practical for me to chop and change appointments. I use an alarm-clock-light that gets gradually brighter to simulate sunrise, which helps, but I also accept that I feel more sluggish in these few months of dark mornings, so I have lower expectations of what I’ll achieve.

But what if SAD really fits my experience?

If you experience severe depression as a result of changing seasons, you’ll probably find it helpful to investigate this with the help of a counsellor or psychotherapist. People severely affected by SAD are more likely to have depression, bipolar or SAD in their family history. This is as likely to indicate inherited emotional dysregulation (patterns of thinking, feeling and behaviour are often passed down through families) as a ‘genetic tendency’. There’s a good chance that, with the support of an empathic other, you can make changes that will help you feel better (and perhaps interrupt the generational cycle too).

While it’s increasingly accepted that there’s no evidence for the ‘chemical imbalance in the brain’ theory of depression, antidepressants can still be helpful for dialling down strong emotions to a point where you can begin to tackle the issues underlying them. There are other self-help suggestions for SAD here .

I don’t believe it’s helpful to assume that changing moods or energy levels are a ‘disorder’. Arguably it could be disordered thinking to believe that we should continue to function in the same way all year round, unless we live in a part of the world that doesn’t have significant seasonal changes.

Even a happy life cannot be without a measure of darkness, and the word happy would lose its meaning if were not balanced by sadness.

Carl Jung

If you find it difficult to tune into what your body is telling you that you need, or if you find it scary or uncomfortable to sit with strong emotions, you may find it helpful to learn Inner Relationship Focusing, which is a self-help practice that supports development of a compassionate attitude towards parts of yourself that you usually ignore. Please get in touch if you’d like to learn more about it, or watch the video on this page.

Further resources