My favourite books of 2024

2024 was a bit of a struggle for me in some ways and I’ve often felt I haven’t had the space I need to find my balance. Perhaps my need for space has grown. However, I notice when looking over the list of books that I’ve read in the year, that one thing that has been prioritised is reading time. It feels good, that I’ve managed to give myself that.

Books can be an escape, a resource for healing, a balm for the soul, an inspiration. As always it’s a bit arbitrary what makes the cut to my ‘top books’ list, and while there are some that were on there without question (Paul Lynch, damn you with your harrowing Prophet Song), I’ve tried to find a balance of books that soothe, inspire and/or entertain.

I’ve read some drivel too – the first book I read last January was so badly written I could barely finish it, even though I was really interested in the subject. But it still amazes me that with so many books in the world I can continue to find something new every time I open a cover. All hail the book!

Here, in no particular order, are my favourite books of 2024:

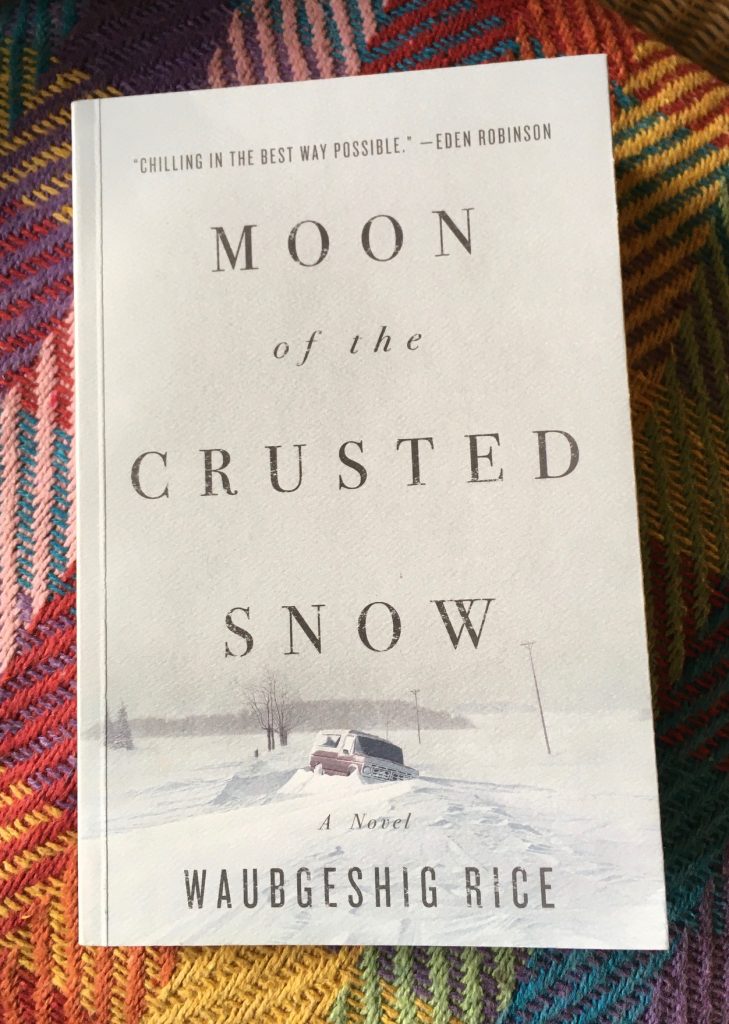

Waubgeshig Rice: Moon of the Crusted Snow

I picked this up in Munro’s Books in Victoria, British Columbia, when visiting friends there. Waubgeshig Rice is from the Wasauksing First Nation in what is now called Ontario, and this book begins in an Anishinaabe community. As you get into the story, you realise it’s a dystopian tale – what happens to a remote community when the lights go out and you don’t know what’s happening out there in the world?

Or is it utopian rather than dystopian? That’s the edge on which this story teeters, and what makes it such a head-expander. For me, the idea of the established order collapsing is pretty terrifying. But if you belong to a community where your way of life was almost destroyed by colonisers, where the land you lived on and with was taken from you and treated as a commodity and where you continue to be disempowered and disadvantaged by the status quo – maybe the collapse of that power isn’t a disaster?

I love discovering a new world through someone else’s eyes, and this book – the first of a series following the same family – really gave me that.

Paul Lynch: Prophet Song

This choice by one of the members in my book group is tremendous and terrifying. Like Rice’s ‘Moon of the Crusted Snow’, the story is set right about now, or in the immediate future. So much of it is familiar – a family going about their day to day life in Dublin. Except that their day to day life is in an Ireland that is becoming a totalitarian state under a far-right government that has suspended the constitution. Lynch has said that he was inspired by the West’s indifference to the plight of refugees escaping the Syrian civil war and the story certainly brings home an understanding of just what that experience might be like.

The story is terrifying enough – or, with the horrific rise of right-wing populism we’re currently experiencing in the world – believable enough to be terrifying. But the style of writing gives it an extra edge – there are hardly any paragraph breaks and sentences run on for ever giving you the feeling as you’re reading it of running to try and catch up with events. I don’t think I’ve ever read a book that had such a bodily effect on me – I felt anxious a lot of the time because of this writing style and goddammit where’s a break so I can put it down!

So not a relaxing read AT ALL – but this may be the most powerful book I’ve read in almost 20 years of book group meetings.

Michelle Obama: Becoming

I’m not much of a one for a celeb memoir AT ALL so even though I’ve admired Michelle Obama’s grace and articulacy (is that a word?) I would probably never have got round to reading this, had it not been offered to me by someone who’s as unlikely as me to pick up biographies of the famous.

But I’m so glad I did. First of all it totally challenged my assumption that you only get to that sort of position if you come from power and wealth. Spoiler alert – Michelle Robinson did NOT have a wealthy start in life, and neither did Barack Obama. Not wealthy in monetary terms at least – and there’s more inspiration in this tale, for just how much difference it makes when you have supportive, nurturing, loving, interested parents, family and community.

The other eye-opener was the detail on just how bonkers life in the White House is, probably even more so if you grew up working-class, and what it was like to try and adjust to that life, from the attempts to make a house with over 100 rooms a comfortable living space, to what happens to a child’s life when she is shadowed by a security team all the time, to the challenge of maintaining a healthy marriage when your husband is never not working and that work has an impact of millions of lives.

A fascinating read.

Hannah Ross: Revolutions

Whether you’re interested in cycling or not, Revolutions – subtitled How women changed the world on two wheels – is a great social history of some of the women who used their bikes to take action to challenge assumptions, taboos and laws. There are some amazing stories in here – such as that of 24-yr-old Annie ‘Londonderry’ Kopchovsky who became the first woman to cycle round the world in 1894. She took on the challenge after two men bet a woman couldn’t do it – even though she’d never actually ridden a bike.

There’s plenty of opportunity to be awestruck at the determination required to break social norms – as well as the physical efforts involved; and of course into the bargain plenty of eye-rolling and for-fuck’s-saking at the ridiculous costumes women were required to wear, the beliefs about the effects of cycling on the delicate constitutions and feeble mental states of female creatures. I did a lot of that laugh-groaning.

If you ARE a woman who loves the freedom of getting out on your bike, this book will make you appreciate it even more.

Josie George: A Still Life

I first came across Josie George reading The Guardian’s nature diary and was really struck by how someone could bring such focused attention to the seemingly everyday. She writes beautifully about the crow in the rain that she watches from her bedroom window, inviting the reader, too, to find it marvellous.

Since childhood the author has lived with disabling, fluctuating chronic illness, and this book – a memoir – was ‘written mostly from bed’. It follows the year from Winter through to Autumn, and weaves between her life now, aged 36, in a wee terraced house shared with her teenage son, and her years growing up. It’s quiet, philosophical, and also full of beauty in her observations of the world around her – non-human and human.

Sarah Winman: Still Life

A lovely, lovely tale that I really didn’t want to come to the end of.

There’s a tremendous cast of characters who move in and out of each other’s lives over four decades from the end of the WWII. It ranges between Tuscany, and London’s East End, and back to Italy – to Florence this time – touching on beauty, love and community. I ended up caring deeply about the people in it.

Although it deals with loss and love that goes against accepted norms of the time, it’s also a gentle, sweet book – an easy read in the best possible way.

Merlin Sheldrake: Entangled Life

How to describe this book? I mean, essentially, it’s a book about fungi. But saying that doesn’t convey the mind-bending stories of fungal life that it contains. This is a book not just about natural history; it’s also a sort of philosophy text, exploring how humans look at things, our interpretations that stem from our biological structure and processes, and how fungi can help us look at things differently because of their structures and processes that are so very very different.

This book was the ‘read-aloud’ book in our house for the winter*, because it’s so entertaining and full of ‘what the hell?!’ moments. There’s some quite dense sections in there but Sheldrake’s writing is so easy to read that it’s not a difficult read. It also has more notes at the back than possibly any book I’ve ever read, but some of those notes – going off into the unexpected way in which a particular discovery was made, for example – are also good fun.

*the last couple of years my partner and I have had a book that we read out to each other on occasional evenings by the fire. Who said you have to grow out of reading aloud?

Kate Raworth: Doughnut Economics

I never thought I’d be recommending an economics textbook. In fact it SHOULD be a coursebook, if it’s not. It’s a mind-blower and completely changed the way I think about how the world works and made me realise how many assumptions I had about ‘this is the way it has to be’. The doughnut, by the way, is the framework for considering an approach to life where humans don’t overshoot the ecological ceiling (the outside of the doughnut) while at the same time ensuring ALL people have enough of life’s essentials (without falling into the hole in the middle).

The person who recommended this book to me said it’s “a great read if you’re pure raging that like 3 men just invented how the whole world works without including in their economic modelling any labour typically done by women, and you’d like a more hopeful alternative to think about”. I can’t say it better than that – economics isn’t just for beardy old white men.

Jenni Fagan: Hex

If you like short books, this is for you! It punches above its weight in terms of impact. One from a ‘retelling history’ series published by Birlinn books, it touches on the North Berwick witch trials that were a scourge and a shame of Scotland in the late 1500s, and that had a brutal impact on hundreds of women, and the communities around them.

The novel takes place in the cell of a teenage girl, Geillis Duncan, convicted of witchcraft, on the night before her execution, where she receives a visitor from the future who offers her support and solace. It brought the events of hundreds of years ago right up to date for me, as I imagined what it must have been like to be a teenager powerless at the hands of men who objected to women having skill, talent and knowledge. A gem from a writer who never disappoints.

Val McDermid: Queen Macbeth

The launch of this book saw Val McDermid being interviewed by Nicola Sturgeon; two very articulate women who don’t take any shit, which made for a great (and funny) introduction to this book.

Like Hex, above, this is in Birlinn’s series of Darkland Tales, where “the best modern authors offer dramatic fictional retellings of stories from history, myth and legend”. If you’re familiar with McDermid’s crime thrillers, this is nothing like them – but it’s a gripping page-turner nonetheless.

The Queen in this tale is completely unlike the witchy power-behind-the-throne character that Shakespeare gave us. This is the first queen of Scotland, on the run with her three companions, a healer, a weaver and a seer. They are tough, strong and clever and an ode to the power of female solidarity. Above all, this is a great yarn.

Elizabeth Tova Bailey: The Sound of a Wild Snail Eating

The title of this book is irresistible and it’s been on my list for ages since someone told me about it. I finally bought it at the same time as A Still Life by Josie George and, like that, it’s written by someone whose health challenges reduced her ability to access outdoor spaces.

It’s wholly lovely – the quotations that open chapters (where snails have entered the world of literature), and the delicate pencil drawing illustrations, really complement the text. Bailey was forced to remain in bed due to a debilitating illness and a friend brought her a snail which initially lived in / on a plant-pot, and then in a terrarium. She closely observes the life of this individual and so this book is so much more than ‘a study of snails’ – it’s a study of this particular snail. Her curiosity when it hides, or changes its behaviour, prompts her to learn more about snails in general, but it’s the relationship with this small part of the natural world, and her own world crossing over with it, that make this such a special little tale.

Dougie Strang: Bone Cave

Anyone who knows me, knows that I love solitary explorations into remote places, so this book was always going to appeal to me. The author spends a month in autumn walking and travelling through western and north-western Scotland – but doesn’t follow established routes or marked Ways.

“Instead, I used stories as waymarks – folktales and myths, primarily from Gaelic tradition – and I made my way between the places that held those stories according to chance and circumstance.” These stories are woven through Strang’s present-day account of the walk, and seem to influence his wish to move fast or slow at different places on the journey. Sometimes he’ll hitch a lift, or move briskly over a mountain in the gathering gloom; at other times he camps for 3-4 days in a quiet spot, slowing down, spending his days gathering scraps of wood for a fire.

In a year when I haven’t got out away from people very much, this book reminded me how wonderful it can be to get out into the more-than-human world and simply be.

Sathnam Sanghera: Empireland

Whether fact or fiction, I love reading things that challenge my assumptions, that remind me that what I see as ‘it just is like that’ always has its roots in something.

This book certainly does that. We often think of the British Empire as a thing of the past – depending on your perspective, something to be proud of (I know, probably not my target market) or something to see as a regrettable aspect of UK history. Empireland drills down into how aspects of what we consider to be ‘modern Britain’ are rooted in its history of empire-building.

It could be – and is – a heavy subject, but Sanghera writes with a dry wit that makes it a book that is, if not comfortable to read, then certainly not difficult.

RF Kuang: Babel

A novel that takes place within the context of empire-building – this time in a kind of parallel universe, which reminded me a little of the world in Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials books, perhaps because of the central role that the alternative Oxford University plays in it.

The tower of Babel in the book is the university’s institute of translation – but there’s more than just understanding other languages involved as Babel is also the centre of magical power via the use of meanings that are lost in translation, and this power supports the imperial quest for colonisation.

There’s a fantastic diversity of characters and the plot swirls around a group of new students at the institute, and their increasing awareness that their academic efforts support Britain’s imperialist white supremacy. A gripping, entertaining read.

Susan Jordan: The Box

This is a story of people putting their lives back together. The two central characters are Richard – whose wife, Kate, has died suddenly at the age of 40 – and Jo, Kate’s twin sister, who Richard had a brief relationship with before he and Kate met. The box in question is that containing Kate’s ashes, which Richard is trying to figure out where to scatter.

The novel alternates between the perspectives of Richard and Jo as their lives move toward and away from each other. It’s a sensitive portrayal of the unpredictability, upheaval and messiness of grief, as well as, in Jo’s case, an exploration of hope and finding a way forward from mental health struggles and trauma. The author is an experienced psychotherapist, but this at no time reads like a case study, it’s a simply and compassionately-told tale.

Hwang Bo-Reum: Welcome to the Hyunam-Dong Bookshop

After burning out doing all the things that she was expected to do to ‘succeed’ in life, Yeongju follows her dream and opens a bookshop. This is a story of normal people living normal lives – there’s no major drama or adventure. All the characters have experienced disappointment and have doubt in themselves, and as the book unfolds, they begin to find their ways, that may contradict what traditional Korean society expects of them.

It prompted me to wonder, what is ‘a life lived well’? And how different the things are that bring meaning and contentment in life are from one person to another.

A gentle book about people finding their places in life.

Nicola Chester: On Gallows Down

An achingly beautiful, heartbreaking book – the book I wish I could write! – this is a wonderfully-crafted nature memoir and more, covering rural protests and political activism. The author finds refuge in nature as a child, protests the devastating loss of ancient trees as a young woman, attempts to give her children a good life in insecure tenanted homes on large estates.

Chester is utterly rooted in the landscape where she grew up and lives her adult life – the North Wessex Downs, Greenham Common. She pays exquisite detail to the wildlife around her, from the songbirds to the badgers she takes her young children to see. She finds hope in the rewilding of Greenham Common. And she doesn’t gloss over the terrible grief of really attending to the world around you and seeing the disregard paid to the creatures we share our planet with. Beautiful.

Emma Dabiri: Don’t Touch My Hair

For the last decade plus, I’ve reverted to a hairstyle that takes as little time and input as possible – I just can’t find it in myself to care. But even when I had long curly locks, they didn’t take a lot of looking after – and anyway, I live in a country where easily obtainable hair products were more-or-less geared towards hair like mine.

This is a fascinating read that links Dabiri’s own experience of taking care of her hair – as a girl brought up in Ireland, with a white mother – to a history of black hair and hairstyles, encompassing slavery, community, women’s friendship, social media. Towards the end she explores the role of indigenous fractal mathematic systems in black hairstyles, which just about blew my mind. An amazing education that’s crucially also an accessible read.

Sarah Perry: Enlightenment

This was a popular read this year in our bookgroup. The notes on my book-list say ‘wonderful from the start’. I realise that I’ve been thinking about it as a ‘historical novel’, but actually it’s set now, following the lives of two unlikely friends over twenty years. It’s partly the nature of some of the people that give it a feel of another time, and partly that two of the characters are obsessed with a nineteenth-century astronomer who seems to have disappeared.

Definitely a story for winter, to curl up with and lose yourself in – much of the action takes place after dark and is interspersed with star-gazing. The characters are wonderfully constructed and while I felt there’s a sense of melancholy to the book, it’s also ridiculous at times. Completely immersive.

Andrew Miller: Now We Shall Be Entirely Free

Oh, I just loved this tale. It’s a real page-turning adventure yarn with flavours of Buchan or Stevenson or Du Maurier. It’s set in the time of the Napoleonic wars and gives a very different flavour of the utter carnage and chaos that must have been, if you’re used to Jane Austen’s treatment of the handsome soldiers wandering about town on leave.

So far, so fascinating, but then the plot turns into a flight to Scotland and the Hebrides, with the main character, Lacroix, pursued by a sinister and terrifying English corporal teamed up with a Spanish officer. I was slightly distracted by the attempts to figure out just which islands they’re landing on, but the feel of the landscape and the contrasting lives of Glasgow and the Islands are a wonderful addition to the thrill and terror of the hunt. A ripping yarn!

Bethany Rivers : The Sea Refuses No River

I get lost in novels and I’m moved by nature memoirs. But sometimes it’s only poetry that can convey or capture the feel or sense of an emotion. I don’t really know how to write about or ‘review’ poetry as I can’t always tell what I like about it – I seem to experience it in a less cognitive way. Or perhaps I don’t have enough practice.

So, I will just say: I liked this collection of poems. And here’s one for a taste:

February

February is a plank of wood

between darkest winter and the beginning.

You can be forgiven for

not looking as you crawl along,

pushing your candle slowly out in front,

your scarf of many colours double-layered.

A survival month: the well is still

empty, and you’ve yet to find the food

that nourishes. The plank is narrow

and stretches across streams and grass-lands

your feet dare not touch. The plank

is slippery: your hands grip both sides,

sliding one in front of the other,

one in front of the other.

If you too love books you may well have a list as long as your arm already (I now have different categories of books-to-read in a notebook, but they still seem to grow ten times as fast as I cross titles off).

Nonetheless, sometimes it’s nice to jump into someone else’s choices. If some of these have appealed to you, check out my reading recommendations from 2023 and 2022.

Happy reading!