What happens in therapy? – PART 1

The practicalities of counselling

I decided to write this blog for anyone who’s wanting to get an idea of what to expect if they start counselling.

The questions ‘What happens in counselling?’ or ‘How does therapy work?’ can be answered in different ways so I’ve split this blog into 2 parts.

- Part 1 looks at the practicalities of starting therapy, and what happens at a conscious level, including the sorts of questions I might ask, setting goals, boundaries, and the control you, as client, have over the direction we go in.

- Part 2 speaks more of what it is that makes talking therapy a useful contribution to helping people to ‘feel better’, touching on the neurology behind psychological healing – the unconscious stuff that’s going on while – and after – therapist and client talk.

I’m writing from my own perspective – i.e. about what’s likely to happen if you and I work together. While much of what I say will hold true for many other psychotherapists and counsellors, there will be variations in the way we work.

What happens in therapy – Part 1: The Practicalities

So………you’re thinking you might find it helpful to see a counsellor. Or someone’s suggested to you that it might help. Or perhaps they’ve told you that ‘being in therapy’ has helped them. What happens when you take the next step, and get in touch?

Initial contact with the therapist

When you contact me, sometimes I won’t have space to start working with you straight away. If so, I’ll ask if you want to go on my waiting list, and I’ll usually suggest some colleagues who may have availability.

Sometimes by the time I get in touch to offer someone on my waiting list a space, they’ve found someone else, which is absolutely fine and to be expected. At this stage, I don’t usually ask you for information other than contact details, until I know we’re going to start working together.

That’s not because I’m not interested in you – it’s because a) I don’t want to hold unnecessary personal information about you unless we actually start a relationship, and b) your situation may have changed by the time I have a place, so the information I gathered is out of date anyway.

Even a brief email exchange agreeing the above should give you a bit of a feel for what I’m like, and at least a hunch as to whether you want to work with me. Forming a working relationship is really important in therapy (more on that in Part 2). If, for some reason, I get on your nerves, it doesn’t have to mean we can’t work together – but no matter how good the counsellor is, sometimes there’ll be personality clashes.

Trust your instincts UNLESS you reach the point where you simply think you will never find the ‘right’ therapist – it may be that something in you doesn’t want to! In which case, try someone – or a few people – who feel ‘good enough’, to get started.

We’ve agreed to start working together – what now?

The dreaded paperwork! I ask people to complete a brief assessment form to check I’ve the experience and skills required, and – if we’re going to be working online – that I believe online therapy is appropriate.

I usually offer a chat over the phone at this stage – sometimes that’s the easiest way for us to compare diaries and find a time that works for both of us, and I can take some assessment notes at the same time, which some people prefer to the form-filling.

We’ll also talk about HOW we’re going to work together. At the time of writing this blog (early 2022), I’m offering:

- online counselling via Zoom video call, instant messaging and email;

- tele-therapy / phone counselling;

- walk-and-talk therapy – counselling while walking outside.

If you’ve decided you want to work in-person with somebody in a room (the ‘traditional’ way of counselling) I can signpost you to other people who may be able to offer you this.

Again, this is an opportunity for you to get a sense of what it might be like to have sessions with me. If we decide to go ahead and book a first session, I’ll send you an agreement or contract to read over, complete and sign. The agreement goes over practicalities like fees, privacy and where/how to complain if you’re not happy. There’s no requirement to commit to a certain number of sessions.

What happens in our first counselling session?

There are a few areas I usually cover at the start of the first therapy session (e.g. confidentiality, cancellation policy), which are also in the written agreement – I go over them again because I think they’re important. At the end of the session I’ll check with you how the experience has been, and whether you want to continue; we’ll confirm further details, usually agreeing a review point after the first 5 or 6 sessions.

In between the beginning and the end, though, the first session varies greatly depending on you. You might have a very clear idea of what you need to ‘get off your chest’ and the relief of having a space where you can do that means that you don’t need any help to get started. This can be especially true if you don’t have much opportunity to talk to other people about how you feel, or if you’re anxious about burdening people by telling them.

At the opposite extreme, you might not know where to start. If that’s the case, then I may ask you some questions…………..

Things the therapist is likely to ask about:

More information about why you’re seeking counselling

-and why now? Has something changed or brought things to a head?

Your previous experience of therapy

If you’ve had therapy before, I want to know what you found helpful or unhelpful, partly because I don’t want to do more of the unhelpful stuff, but also so I can look out for similar dynamics repeating in our relationship so that I can flag them up and we can talk about them; they might be a feature in relationships in your life generally, so we could learn something from them.

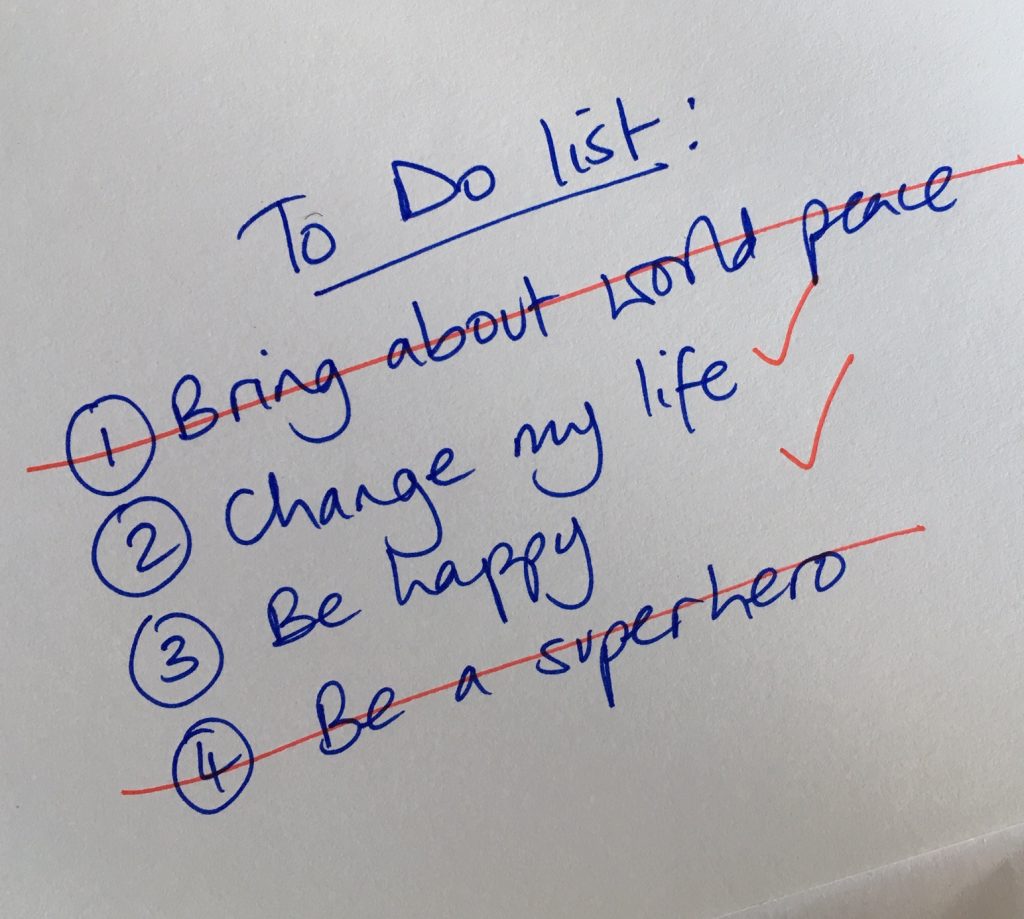

What do you want to GET from counselling?

If this is where you are now, where do you want to be? You might not know at this point, in which case we’ll come back to it at some point down the line.

Your current circumstances

Your living situation, significant relationships, occupation – this helps me understand things like support networks that you have available to you and factors that might contribute to your overall wellbeing.

Your family of origin

Information about what it was like for you growing up can be really useful as it’s likely to influence your behaviour and relationships as an adult, and getting more understanding of ‘no wonder I do this when I had that experience as a child’ can help you be more forgiving and compassionate to yourself.

Lifestyle and self-care patterns

Mental and emotional health is completely interwoven with physical health; there may be changes you want to make at a practical level that will help you mentally.

Anything that feels important to you about your identity or sense of self

You may have a very strong sense of who you are – or you may not know at all.

All these areas may have a bearing on why you’ve decided you want to have therapy, and talking about them can help you better understand yourself. We might not get to any of them in the first session, but I’m likely to ask you more about them at some point.

Reviewing how it’s going

It’ll take us at least a few sessions to settle into a rhythm and get used to each other. I normally suggest that we review how it’s going at session 6 (assuming that you’ve decided you want to carry on that long).

I’ll ask you how you’re finding the experience and I’ll share things that I’ve noticed – patterns that we get into, things I’ve not asked you – to see if they feel significant. I’ll want to know what has felt helpful, but I’ll also ask what has felt challenging or unhelpful, and what you think I or we might do differently – for example – do you find it difficult to stay on topic, and want me to flag up when you’re going off on a tangent? Do you feel as if you’re trying to guess the ‘right’ answer when I ask you questions?

Contracts and goals for counselling

I see my role as being to help you change. That might be:

- making changes in your life

- changing the way you respond to situations, circumstances or people

So, when we review how it’s going, I might ask what you want to change. Sometimes people find this a difficult question to answer – either because they don’t know, or because voicing what they want to be different, out loud, feels risky. But that’s useful information for both of us, too, as there isn’t a right or wrong answer to this question.

You’re the expert on you, and it’s your right to direct the course of the therapy. It might be that I’m not prepared to agree to work towards the change you want, in which case I’ll say so (gently!) and why. Usually this will be because I don’t think the particular change is within your – our – power.

For example

You might say you want to change the way other people treat you.

I’d point out that we can’t make that change as you don’t have control over other people’s behaviour, and suggest that we could focus on changing how you respond if other people treat you badly.

This might involve, building your confidence in speaking out; choosing not to engage with such people; or developing your self-compassion when you feel bruised by the behaviour of others.

And if my suggestion doesn’t feel right for you, we can carry on negotiating, or we can agree to park it and come back to it. From time to time I might check with you whether the goals we’ve agreed are still relevant or whether they need tweaking.

Is it just the client talking and therapist asking questions?

To an observer, a counselling session might look like two people having a chat. It’s known as talking therapy, after all. Often at the start of our relationship, a large chunk of sessions might be you telling me your story – what’s caused you to get in touch. Early in therapy, I’ll probably ask you more questions about your life now, and your history, as I try to get more of a sense of who you are and the influences that have shaped you.

I don’t tend to give advice and certainly don’t tell you what you should do. But equally, I don’t hold back on information which might be useful to you, and so will sometimes share models to help you understand your thinking or behaviour patterns, or introduce some basic neuroscience – this can be helpful in reassuring you that what you see as ‘something wrong with me’ is often a normal biological response to past experiences.

I might also share exercises for you to try inside and outside sessions. Sometimes we’ll agree homework tasks that we can discuss from session to session.

Sometimes I teach a practice called ‘Focusing’ (read about it here) during a session. This is somewhat similar to mindfulness. It can be really helpful as a way of learning to respond to very strong emotions in a way that doesn’t involve avoiding them or being driven by them; instead, you can learn to acknowledge that they’re there and ‘sit next to them’ which can help lessen the intensity of overwhelming feelings.

Doing this in session means that I can help you pace how you do this, a little at a time, especially if you find the thought of engaging with strong feelings, such as anxiety, shame, or fear, is really scary, and worry that they’ll take over – using the session as a space to practice in can be helpful.

Focusing can also be helpful when you’re not sure how you feel, or when you feel numb – it can help you tune in to the feelings that really will be there, below the surface.

Talking about boundaries

The counselling relationship is a very specific one, like no other. We’re often sharing things that are really intimate, revealing the most vulnerable parts of ourselves. And yet this is happening within one 50-minute session, once a week (or whatever frequency we agree).

I’m firm about the boundaries of the relationship, both for the client and for myself. When we sign our agreement to work together we’re also agreeing the parameters within which that takes place. I don’t engage in conversations outside sessions, other than administrative ones where something unforeseen happens and one of us needs to rearrange the session.

This doesn’t mean that I’ll ignore you if you contact me, and it doesn’t mean that we can’t agree extra sessions sometimes if you’re in distress, but – as I don’t offer a crisis service – in general, we’ll keep to the principle that therapy takes place within the session time boundaries.

This is partly because I take my responsibility as a practitioner seriously, and that means taking my own self-care seriously; I’m not good at multi-tasking and need to keep my work and leisure time separate.

But it’s also because many clients I’ve worked with, struggle to maintain good boundaries, which can lead to various difficulties, such as burning out because you can’t say no when someone asks you to do something. My maintenance of boundaries models to you as a client that taking care of oneself is important; this is much more effective therapeutically than simply telling you that boundaries are important without practising what I preach.

In Part 2 of this blog I’ll talk more about how ‘modelling’ by the therapist is a key part of the effect of talking therapy, as well other aspects of how the therapist and client relate, and I’ll delve a bit further into the internal changes that take place during the therapeutic experience.

Everyone’s experience of therapy is unique because every relationship between two people is unique. If you want to know more about what it might be like for you to work with me, please get in touch and we can have a chat.