My favourite books of 2022

I love reading, it’s one of my great joys in life that I feel really nourishes my soul.

In 2021 I started keeping a note of the books that I read. I planned to share my 10 top books of 2022 in the run-up to the year-end, but I could only narrow it down to 20.

I shared these 20, in pairs, over the last few days of 2021 – but I thought I’d gather them all together in one place here too – so that I’ve got them somewhere to remind myself!

Please note these aren’t specifically therapy (or self-help) books – there were some of those, but I haven’t included them here.

In no particular order!

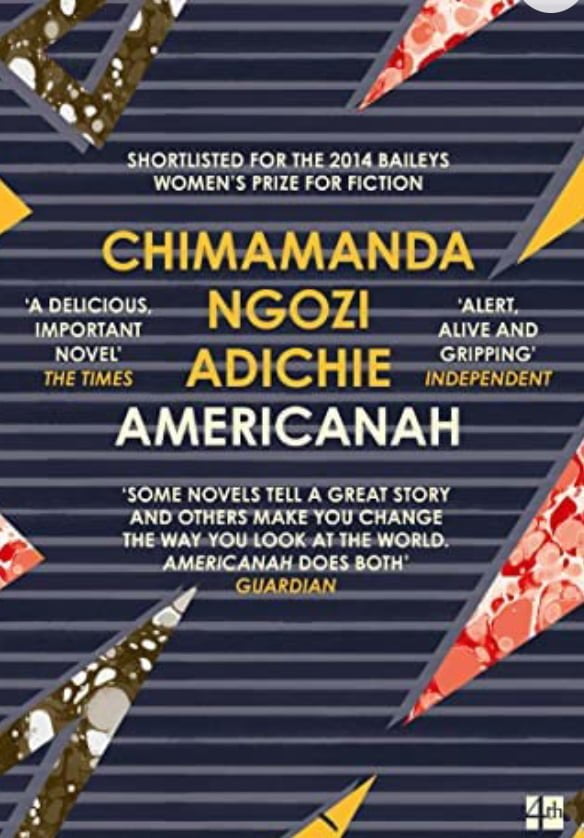

Americanah by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

A wonderful immersive story moving from Nigeria to the US and back again. Ifemelu moves to the United States to study, where she encounters racism and for the first time, discovers what it means to be a “Black Person”. One of those that I didn’t want to put down and also didn’t want to end.

The Wild Silence by Raynor Winn

A friend recommended Raynor Winn’s first book, The Salt Path, after my first solo wild-camping-walking expedition (and if you haven’t already read it, start with The Salt Path). The Wild Silence continues Ray and Moth’s story as they try and find a place to settle and feel safe, after enforced homelessness in middle age. It’s a memoir, and Winn’s voice is just so bloody authentic.

Piranesi by Susanna Clarke

One of this year’s Bookgroup books, Piranesi is mysterious, eerie, magical. I still have vivid mental pictures of the ‘house’ in which the book takes place – an ocean-filled Roman temple that is invaded by tides twice a day. The reader gradually learns more about how Piranesi comes to be there, becoming more emotionally attached in the process.

The Library of the Dead by TL Huchu

A great romp through a dystopian Edinburgh, following the main character, Ropa, a teenage school drop-out who makes ends meet talking to ghosts. It almost feels like Young Adult literature except some of the events are just too gruesome. Great fun for anyone who knows Edinburgh and can picture the entrance to the Library via the Old Calton Burial Ground……

Feeling Heard, Hearing Others by Rob Foxcroft

This is a book about Focusing (and if you don’t know what that is – check out my blog: What is Focusing?). It’s kind of a how-to… and also isn’t really. It’s not really a self-help guide… and it is also helpful and therapeutic. I wasn’t sure whether I liked it at first, the structure and pace is so unlike other books, as is the tentative nature (there are no rigid guidelines here) and the mixing of poetry through the prose to try and convey another sense of what the writer is wanting to express. But I realised that it has similar qualities to Focusing itself; everyone will respond differently, some ideas can’t be captured easily with words, it requires both the speaker (writer) and the listener (reader) to engage, to find a way of meeting or making contact ‘enough’.

English Pastoral: An inheritance by James Rebanks

The word ‘elegaic’ was made for this book, which is a beautiful ode to a landscape by one who is truly hefted to it. James Rebanks is a Lake District farmer who inherited the family hill farm. As a child he watched farmers around him turning to new ‘improved’ methods and saw the destruction of the fabric of the soil, and the disappearance of the creatures living in, around and through the land; in middle age he is returning his land to something closer to the natural/human-influenced state that had evolved over the previous centuries. If you read this, keep going through the middle section of heartbreak; hope does return.

Paradise by Abdulrazak Gurnah

This book gives an experience of a very specific place in time, one which was completely new to me. The young boy who’s the main character is transferred from his rural home to urban East Africa in bonded servitude as payment of his father’s debt, and then has to adjust to European colonialism and its upheaval of existing social hierarchies.

All the light we cannot see by Anthony Doerr

This novel is also in a very specific place in time – that of occupied France in WWII. It follows the stories of a blind French girl and an orphaned German boy whose worlds collide, and is hauntingly beautiful with wonderful imagery and language. I really didn’t want it to end.

Natives: Race & Class in the ruins of Empire by Akala

OMG. It’s brilliant. When looking for ways to educate myself about racism, it’s easy sometimes to get distracted by offerings from across the pond, and then to be frustrated when things don’t seem to fit or have the same relevance. Someone on GoodReads says this is ‘essential reading for anyone British or who wants to understand Britain’. Akala uses his own experience to drive the narrative to brilliant effect. It’s also so chockful with information and references and ‘things I want to know more about’ that I could probably have spent the whole year just being led on to other books by it.

Joseph Knight by James Robertson

A different angle on the intersection of colonialism, empire-building, race and class. You may not know (I didn’t until a couple of years ago) that Scots made up a disproportionately high percentage of British-born plantation owners – Scottish cities owe a lot of their beauty and wealth to the proceeds of the slavery. Joseph Knight was brought to Scotland by his ‘owner’ and eventually successfully gained his freedom in the Edinburgh courts. This true story has been turned into a historical novel by James Robertson – it has the flavour of Scott or Dickens, though I’m not sure they would have given as much credit to the strong female characters.

Silence is a sense by Leila Al Ammar

A novel I picked up by chance in the library, Silence is a Sense is narrated by a young woman who has lost her ability to speak following a long, traumatic journey from Syria to the UK, and begins with her observing the lives going on in other flats in the tower blocks around hers. She begins writing anonymously for a magazine, and the book uses fragments of emails and articles to put her story together.

Invisible Women by Caroline Criado Perez

From silent to invisible. This is a book I’d been meaning to read, but was afraid it would make me furious. When it was chosen for our Bookgroup I read it. Guess what? It made me furious. It picks apart every single aspect of life and carefully and forensically demonstrates just how data bias perpetuates systemic discrimination against women. Public transport. Car safety (crash test dummies being based on an ‘average male body’ meaning that women are at far greater risk of injury and death than men, for example). Sport. Health. But really – it’s a book that any man SHOULD read (you’ll be furious too, generic male, but not as furious as me), because men are needed to change this.

Diary of a young naturalist by Dara McAnulty

My list of books read, says in brackets after this one ‘one to return to for spiritual guidance’, which makes it sound like some religious treaty. The book is drawn from Dara McAnulty’s journal, written over his 15th year. He’s autistic, and finds solace in the natural world when the neurotypical human world becomes too overwhelming, and this in particular spoke to me; that at times when I find myself despairing because of the uncaring of human beings, I can retreat to nature. His ability to look at the tiniest bugs and creatures and lose himself in their worlds is inspiring for people of any age.

Children of Time by Adrian Tchaikovsky

From tiny bugs to big bugs – that’s all I’m saying. This book is mind-bending, amazing – I saw it described somewhere as ‘evolution-based science-fiction’ which is right enough. There’s a whole world, a civilisation, that develops through the book, alongside a bunch of astronauts from a fucked-up Earth travelling through space for all that time. You read /hear about suspended animation all the time in sci-fi, but the way it weaves through the story, with different people having to wake up to do stuff at different times, the way they age at different rates as a result… it’s tremendous, adventurous fiction that Really Makes You Think.

Underland by Robert Macfarlane

Robert Macfarlane is right up there with my absolute favourite authors of all time, the way he writes about landscape is just so beautiful and lyrical. This latest book of his is about underworlds – literal, mythical, literary. Unlike many of his other books, I felt happy to be an armchair traveller with this one; I do not want to do that potholing shit where you have to hold your breath to get round a u-bend in a cave in the hope that there will be air on the other side.

Wanderlust: A History of Walking by Rebecca Solnit

Somebody recommended this to me a while ago and I’m so glad I read it at last. Solnit writes about the relationship between thinking and walking, and walking and culture… taking in pilgrimages and urban strolls. Beautifully written, I’ll be looking out for more Rebecca Solnit.

David Mogo Godhunter by Suyi Davies Okungbowa

I’m getting to know more African speculative fiction – there’s some exciting stuff out there, of which this Nigerian god-punk novel is just one. This is set in a dystopian future, but one where the Orisha War caused thousands of deities to come down onto the streets of Lagos. David is a demigod who needs to, essentially save the world. The environment of the book is vivid and terrifying, and very visual – I could imagine this being made into a blockbuster or a Netflix series with lots of CGI and special effects.

Dark Hunter by FJ Watson

A book set in a place I know to some extent (Berwick-upon-Tweed) but at a time I’ve never given much thought to – the young squire, Benedict, who narrates the story is with the English-held garrison here, in 1317, 3 years after the Scots were victorious at Bannockburn. Much of the time they are under siege, hungry, bored and homesick. There’s lots of chat about the savage Scots. To make things exciting, however, Benedict has to solve a murder. A good rip-roaring page turner.

Our Homesick Songs by Emma Hooper

This was the first book I read in 2022, sent me by a friend. It’s a lyrical, wistful story of a family in a small village in Newfoundland in a time where fish stocks begin to dry up and people have to move away to find work elsewhere. The place, the landscape, the time, play just as much a part in the story as the characters.

The Sea Road by Margaret Elphinstone

…and the last book I read. Margaret Elphinstone is a recent discovery for me and I love her storytelling that immerses me among peoples and times that I’ve never considered, opening my mind wide open. The Sea Road, based on a real person, tells the tale of Gudrid, an Icelandic adventurer (who of course never got a saga because she’s a woman) who travels ‘outside the world’ to what would later be called Newfoundland.

Do you read to relax? To escape? To learn? Because you feel you should?

If you like reading but don’t let yourself loose on books as much as you would like, check out my blog 7 ways that reading books can improve your life – it might encourage you to give yourself permission.