A sense of belonging

I had a weekend away recently with friends, in the Lake District, not far from where my parents had lived in Kendal. I felt ambivalent about being back in an area that had been very familiar to me for a large chunk of my life.

I made a detour on the way home, to visit my parents’ grave in Kendal cemetery. I hadn’t been to the grave since shortly after Dad was buried when I’d checked on the completed headstone, about 11 years earlier. I hoped this time not to find ‘something wrong’ with the grave (damage of some sort) that I would then feel a responsibility to do something about.

Settling into an ecosystem

There was nothing wrong. It was good to see the headstone, no longer new, settling into the landscape. Plastic flowers, that littered so many of the surrounding graves that had sprung up since I was last there, were a jarring contrast to the gently rolling grassy slopes and mature trees.

There were no flowers of any kind at Mum and Dad’s grave, of course, but the stone stood in a rich cushion of golden-green moss that dominated the turf. The rough top had been colonised by more moss, plus a variety of lichens. The face was blackened and streaked – weathered by rain trickling down – and more moss was beginning to take hold in the lettering, tiny clumps in the first and last lines of the inscription. We’d chosen a stone made from a slab of Lakeland slate, endemic to the landscape and buildings of the area. The headstone looked as if it belonged, as if it was being absorbed into an ecosystem.

Afterwards, we walked into the town, along half-recalled routes – ways that had been familiar but not now travelled by us for a decade. It was nearly midday as we passed the town hall, and I remembered to pause and wait for the tune to play on the bells. Familiar, familiar tune – I had a fleeting, vivid memory of hearing the chimes from Mum and Dad’s house on Fellside. We stopped for lunch in a pub that had been refurbished – probably more than once – since I’d last been in there. And then I headed off to the railway station, to wait on the bleak, windy platform that I associated with visits to my widowed father in his sheltered housing.

Human connections

It felt good…..right………..helpful – I’m not sure what the word is – to have gone to Kendal. Not necessarily good to go, but to have gone. I realised that I’d been avoiding it, and that this was something to do with not knowing who I was, there, any longer. I felt as if I’d lost some sort of ownership. While Mum and Dad were there I hadn’t belonged – it wasn’t my place, I’d never lived there – but I had had a connection, a ‘right’ to be there. When I thought of going back, I was a tourist.

The visit there to bury my father, who’d moved to be closer to us shortly before his death, came to mind – the large house that me and my siblings had rented to have somewhere to be together, and how that felt so different from staying in the family home after Mum died. The ‘family home’ that had never been home to any of us – but which nonetheless had some of the qualities of ‘home’ because of our parents’ presence.

I wouldn’t stay there for more than a week or two at a time, yet for many years it had been a retreat, a place where I could relax, push worries and stress to the back of my mind and be looked after. Until it wasn’t. As my mum was dying, it became a place to be reminded of sadness, and to attempt to be the one doing the looking after, and a place where she died, and a place where I grieved, and a place where I felt helpless in the face of Dad’s pain, and a place to be cleared out as we moved my father into his new and different home.

The right conditions for growth

This time, I returned home to my Scottish fishing village (I wrote ‘home’ there without even thinking). The next morning, as usual, I started the working day with my ‘commute’ – a 10 minute stroll along the sea and back. As I walked by the harbour I was reminded of my decision that “I choose where I belong”, that I chose to belong to Cockenzie. I made that choice with a fierceness when I returned from two years living in Italy where I had felt unrooted and adrift, with a sense that I was consciously committing to the place where I had gradually put down roots and made connections without quite noticing.

As I sat down to work, I noticed the contact between my body and the chair, my feet on the floor, noticed that I felt solid and grounded, and the thought “this is where I’m choosing to belong at the moment” came. With that thought, came another – if I’m choosing this now, then I can choose to belong to somewhere else. We’d been talking about this recently, prompted by my feeling hemmed in by the increasing urbanisation of the land around us, my distress at local ecosystems being bulldozed and cleared, feeling so powerless to stop it that I wanted to escape instead.

I noticed a fear reaction in my chest. Something in me was afraid of being in a place where no one knew me. This sense was, very clearly, not about lacking social activity, but of not being ‘known’, a kind of subliminal sense of being recognised and acknowledged and seen, of people caring about me. I had a sense, as I imagined living somewhere else, of being untethered, without the fine strings that connected me to people in the vicinity.

An image came to mind of roots being put down. Not thick tree roots finding cracks in the bedrock, but delicate hairs and strands, the tiny filaments used by moss to hang on to the carved letters on a gravestone. Part of me – perhaps that part that was afraid of being untethered – thought that if I had put roots down, then this was surely where I was meant to be?

Yet books that I’d read recently – of trees, and moss, and ecosystems, of mammalian safety responses – reminded me that just because this is where the tree-seed has ended up, it doesn’t necessarily mean that it’s the most nourishing environment for it.

What’s best for the tree’s health? If it’s uprooted at a mature stage of its life, how will it cope? Once transferred into a site with better conditions, will the benefits of the added nutrition outweigh the trauma of the uprooting? I found myself disappearing down a rabbit-hole of tree analogy……….”if you’re going to transplant the tree at this point in its life, you have to be really confident that the new site has got the perfect environmental conditions, because it will need time to establish; and to think about the additional care that will be required to help it flourish after the move”……….”wouldn’t it be better to think about what additional material needs to be added to the current situation to feed it where it is?”

What is belonging?

What does it mean to belong? Chambers dictionary gives the definition “to pertain (to); to be the property (of, with, to); to be a part or appendage (of); or in any way connected…..; to have a proper place (in); to be entirely suitable; to be a native or inhabitant, or member (of).”

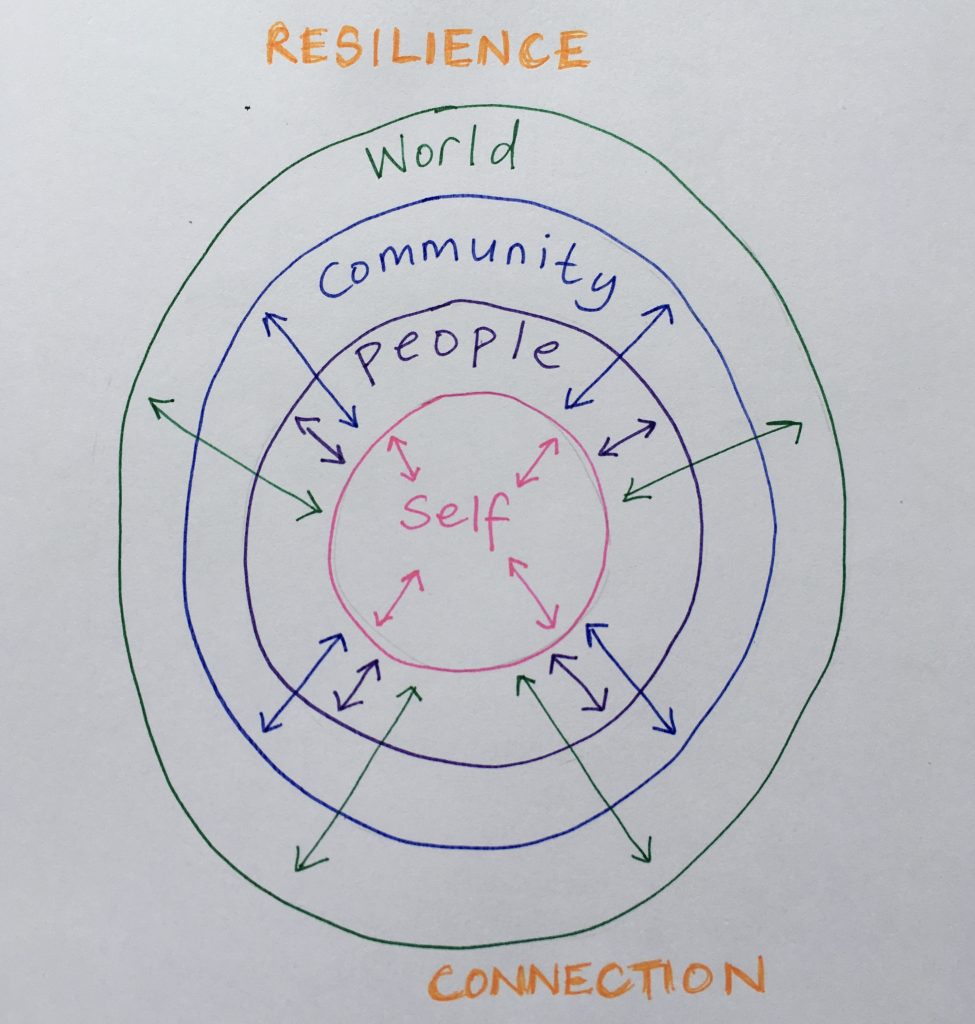

What a myriad of related and yet subtly different meanings. The ‘felt sense’ of belonging is something that we hold within ourselves. Or – is it more accurate to say that many of us hold a yearning for what we imagine ‘belonging’ feels like? The definitions above describe belonging, often, as being within the ownership of another.

Yet a Cornell University definition gives belonging as “the feeling of security and support when there is a sense of acceptance, inclusion and identity for a member of a certain group”. And Carl Rogers, who developed person-centred therapy, said “Belonging is….a unique and subjective experience that relates to a yearning for connection to others”.

These definitions refer to human connection, so important for feeling safe. The feeling I had in Kendal, of not having ‘ownership’, would certainly make sense seen through the frame of human connection, now that my parents are no longer there. Perhaps I’m searching for the wrong thing when I look for a place to belong.

Yet I wonder if these definitions above pay enough attention to our place in the landscape, the connection that our bodies may naturally feel to safe spaces. I remember reading my dad’s diary, where he had recorded 6-yr-old me spontaneously exclaiming how happy I was as we walked in the rolling green hills of North Wales – I can imagine the contrast of being ‘held’ in that space after the excitement of the rocky scrambles of Crib Goch.

Hefted

The Lake District fells are populated by Herdwick sheep, a small, hardy breed that are ‘hefted’. It means that they are tied to a particular area of the land by instinctive knowledge. Of course this doesn’t evolve from nowhere – hefting develops through animals being constantly shepherded in one area until they learn their ‘heft’, and thereafter the knowledge is passed from sheep to lamb through the generations.

I’ve always had a kind of wistful awe of these creatures for whom the sense of where they belong is in their blood. I’ve heard something of it too, in the voices of people whose families have lived in the same place for generations (James Rebanks, author of The Shepherd’s Life and English Pastoral, comes to mind). I can only imagine the depth of sorrow felt by those who have been forced from their lives and homes in war zones, how that forced separation from place layers trauma on top of trauma.

In my family the unspoken expectation seemed to be that we moved far away as soon as possible; certainly that was the example given me by my parents’ generation, and then by my older siblings, most of whom left the country while I was barely a teenager. But although I’ve lived in other places for periods of time, the homesickness that I felt wasn’t just for people, it was for landscape too. I wanted to get back to hills and green and I welcomed the changeable weather that made the Scottish landscape what it was.

I want to not be searching for the ‘right place to be’. Internet searches for ‘how to cultivate belonging’ focus on ‘creating a workplace culture’ (i.e. how to ‘make other people’ feel they belong) or on seeking to connect with others, to look for what you have in common. I recognise that there’s value in that – finding ‘your people’ is important. But there’s two other facets that seem important to me too:

Belonging with myself:

I don’t quite know what this looks like, but there’s something about not trying to escape from where I am (in the hope that I’ll find where I belong), of bringing an attitude of self-acceptance, of listening to and learning what I need, of looking for the smallest steps towards that, of being comfortable with not being comfortable with myself. I know I can trust that the practise of Focusing will support me with this, reminding me that I’m already ‘home’ with myself.

Belonging to the more-than-human world:

The idea that belonging is about people feels so incomplete to me. When I lived in a city I was constantly searching for the tiny patches of scrubby green, for the signs of life in the canals and in the cracks between the stones. We’ve been so conditioned to separate ourselves from the rest of the world, yet something in me withers and starves if I don’t make those connections.

Even my splitting these into ‘myself’ and ‘world’ is another example of that insidious disconnect – I need to allow my mind and body to be one system of belonging, and my body yearns to be with, and belong to, the world.

As I look at the word ‘belonging’ again, I’m struck by how it looks like an action word, yet we see belonging as something that descends upon us while we passively wait. I remember how I returned to my village six years ago with the decision that ‘I choose where I belong’. Perhaps belonging requires me to be active, to apply myself to belonging, to look and reach and attend to allowing the tiny moss threads to attach and connect me to people and place. And belonging is something I will continue to muse on.

References

Belonging definition – Cornell University: sense-belonging

Belonging – Carl Rogers: Making sense of belonging

Hefted: Hefted-flocks-and-herds